Every culture has its own peculiarities, but at the same time, some elements of different cultures overlap in one or the other way. To be sure, Gilgit-Baltistan has its own distinctive and unique culture.

Being a student of literature, it is very interesting for me to trace some elements of Greek culture in my own culture. My concern is neither to indulge myself in the issue of whether we have borrowed our culture from Greeks, or they have borrowed their culture from ours, nor I am intended in degrading any of the said cultures. My basic aim is just to highlight some similarities in both these cultures, in general, and some theatrical similarities, in particular. Obviously, ours is a nascent culture as compared to the ancient Greek culture dominated by towering figures like Aeschylus, Euripides and Aristophanes. Despite having such a huge difference of age, we can find some deep similarities between the two.

This is just a little endeavor of mine to give a clue to the students of literature.

It is a well-known fact that GB is the coldest part of Pakistan with freezing low temperatures. Due to these intense temperatures, all the activities in the region fade in winters. In order to spend their leisure time in an entertaining way, the people of GB arrange some informal but healthy festivals of different types. It may not be entirely wrong to say that winters bring a new spring of life in GB; new dresses, new dishes and new activities are welcomed wholeheartedly by the people of the mountainous terrain.

Apart from indulging in games like Polo, Gilli Danda, they also arrange a very entertaining festival known as Shaap. It is one of the most romantic festivals of GB which is celebrated with a great heartiness in winter. Interestingly, it is arranged on the chilling nights of winter which confines all people to their homes so that each and every person of the family could enjoy it. A well-organized chorus of youth led by a central character named as Shaapae Jaro performs this whole theatrical composition.

Now, let’s have a look into the structure and costumes of this grand celebration. Like the earliest Greek theatre of Thespis, this Shina Festival also has a chorus of people following a domineering single character usually the protagonist (Shaapae Jaro) of the play. As in Athens, these literary festivals were arranged to honor the god Dionysus, the Shaap also has some religious clues, as the chorus and the Jaro bestows the family members with a flurry of prayers. They pray for their health, wealth and nuptial lives. Above all, at the end of this small segment, the Knight of the dramatic chorus performs a dance which makes the play a sister of the Greek Comedy.

Another fascinating resemblance between the two theatrical compositions is their patriarchal structure. In the Athenian theatre, women were not allowed to perform on stage and their roles were being played by their male counterparts attired in costumes of women. In the same way, in the said cultural event of GB, women are not participating and their role is being played by Shapae Jari– a man in the guise of a woman. Similarly, the chorus enchants for the coming of a son in the house visited by them and sometimes they gift a little arrow with a bow to the woman-to-become-mother. This arrow and bow signify the physical strength of man as these were used as tools of war in the Athenian theatre of war. Besides, the drums are used as musical instruments in both these celebrations. In return, as the Athenian thespians were rewarded with different titles and honors for their dramatic performances, the locals of GB honor this traditional chorus of Shaap with some of the precious gifts of the region like Nasalae Moch (dry meat), Ushaar (dry fruits like walnuts, dry apricots, almonds, dry grapes etc) and other fruits like apples, pomegranates etc. These local gifts are considered more precious than money. Even some families lacking in these gifts, give a handful of maize or wheat which the chorus accepts humbly.

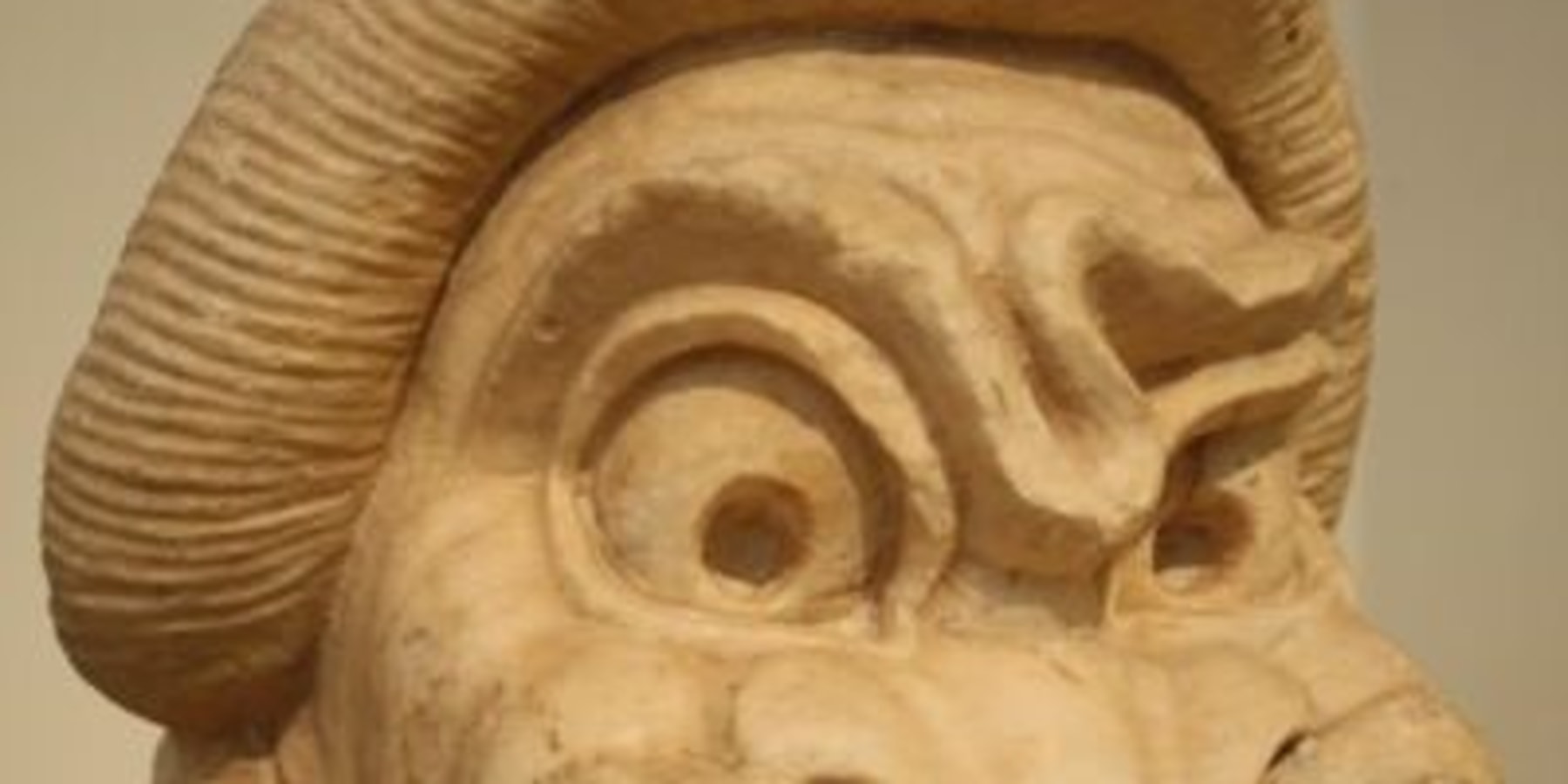

Now let’s have a look into the costumes of these festivals. Since 5th BC, in the Greek theatre, the “Mask” is known to have been used during the times of Aeschylus and considered to be one of the iconic conventions of classical Greek theatre. Illustrations of theatrical masks from 5th century display a helmet-like mask, covering the entire face and head, with holes for the eyes and a small aperture for the mouth, as well as an integrated wig. These masks were used to keep a distance between the actors and the audience and also between myth and reality. Effectively, this demonstrates the way in which the mask was to melt into the face and allow the actor to vanish into the role. Similarly, in our festival, the Shapae Jaro and Jari use to wear masks to hide their real identity. It is the mask which creates curiosity by keeping the actors at a distance from their audience and even sometimes, the members of the same family cannot identify that the person behind this mask is their own member of family. It not only creates curiosity in the audience but also helps the actors to play their designated roles.

More interestingly, in order to play female roles, the characters in Athenian theatre used to wear “prosterneda” (in front of the chest to imitate female breasts) and “progastreda” in front of the belly. To maintain cultural sanctity and domestic decorum, our actors are just dressed like women but not wearing “prosterneda” and “progastreda”. In most of the cases, the actors play the roles of old persons in guise of beggars which are fluent in begging and giving prayers. The hosting family gives an immense respect to these thespians.

Costumes are very important paraphernalia of any dramatic production because they determine the characters by gender or social status. In the early productions, actors have been using body paintings. Little by little they started using animal skins, ears and feathers as in Aristophanes’ The Birds. In the beginning, our actors were also using these animal skins and feathers but nowadays synthetic masks are easily available. Certainly, the use of a mask covering the whole produces an enhanced resonating effect, which serves dramatic delivery. Elizabethan dramatists also utilized these masks as necessary dramatic paraphernalia. Currently, in a local drama Ali Malik, though, there is no mask but the often used wick speaks volumes about the use of costumes in our culture.

In Athenian Theatre, the actors used to put shoes with high heels named as “kothornoi” in Greek. Though, today our actors used to wear ordinary shoes but in the past they used to wear some special kind of shoes made up of the hides of different animals which are called as “Thawti” in our local lexicon of Shina Language. One can see this “Thawti” in the recently launched 7th Episode of the famous seasons The Game of Thrones. Similarly, the long white sleeved cloak known as “peplos” or “chlamys” in Athens has been represented in our culture by a much more sophisticated over-garment name “Shuka” in Shina. By wearing these costumes and paraphernalia, the actors had to renounce their individuality.

In a nutshell, a comparative study can be conducted to find out the similarities between these two cultures. Not only costumes, but also some supernatural characters like Oracles and Prophets of the ancient past still exist in our culture. Witches and wizards can be mentioned here in this regard. The prophecies of our oracles like those of the Greek plays are considered as valid even in this techno-scientific era. The prophecies of “Dayal Khimicho” and other dayals today have some validity in our society. Most of the people believe that with the passage of time, all these predictions will come true. Concluding it all, like literature itself, culture also transcends through space and time. Apart from a huge difference of age, the distance between Athens and GB is more than 4505 km. But the homogenous cultures of both regions produce a cultural proximity between these two cultural hubs.